Your Do-It-Yourself Sestina

I have always found the sestina to be among the most rigid of poetic forms. It’s like an unspooled villanelle minus the rhyme; a wind-baggy sonnet minus the volta. The sestina is the Bobby Knight of poetic forms: a tight sweater shoving words into predetermined zones. It’s the Babel of poetic forms: six wobbly floors on a tipsy tercet. It’s a virtual vertical verbal tower, a linguistic Jenga puzzle. I almost always anticipate failure or boredom when I attempt the sestina. It’s among my favorite forms. In retrospect, it makes perfect sense that I locked onto the sestina at the beginning of quarantine. At the beginning of the Trump administration, the sonnet became a weapon of love and resistance for me in American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin. I can’t say why the sestina or slant-rhyme quatrains got me through the end of that administration, but form was a buttress; poetry, a shelter.

The following DIY sestina (“What Does the Piece Remind You Of?”) was part of three DIY sestinas to be presented at the Phillips Collection Museum in Washington, DC, for the exhibit Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition. When the event was canceled in April 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic, I sent the museum the DIY sestina form so that those who would have been present at the event could try writing their own ekphrastic poems in quarantine. “What Does the Piece Remind You Of?” tracks where six paintings from the collection take me. The envoi of the poem takes a longer look at a single painting by William H. Johnson, an African American painter born in my home state of South Carolina in 1901. In my comments accompanying the poems, I wrote,

If we were together, you might be coming back to your seats after twenty minutes. Maybe you’d have a little pen and paper for notes. You’d say as much as you wish. What does the piece remind you of? What question would you ask the artist? What was used to make the piece? I’d give you another twenty or thirty minutes to make your DIY sestina machines and sestina lines. We’d share.

Since 2020 I have tried a few variations on DIY sestina schemes: a visual Octavia Butler sestina, two title-triggering sestina engines. As in almost every excursion into form, I hope simply to be surprised and challenged. Your own refinements and/or exaggeration of the DIY sestina’s possibilities will hopefully launch you into your own poem-making. The results need not be sestinas. I aim to function as a kind of coach, setting up some tasks for willing participants ... maybe don’t send me your sestinas.

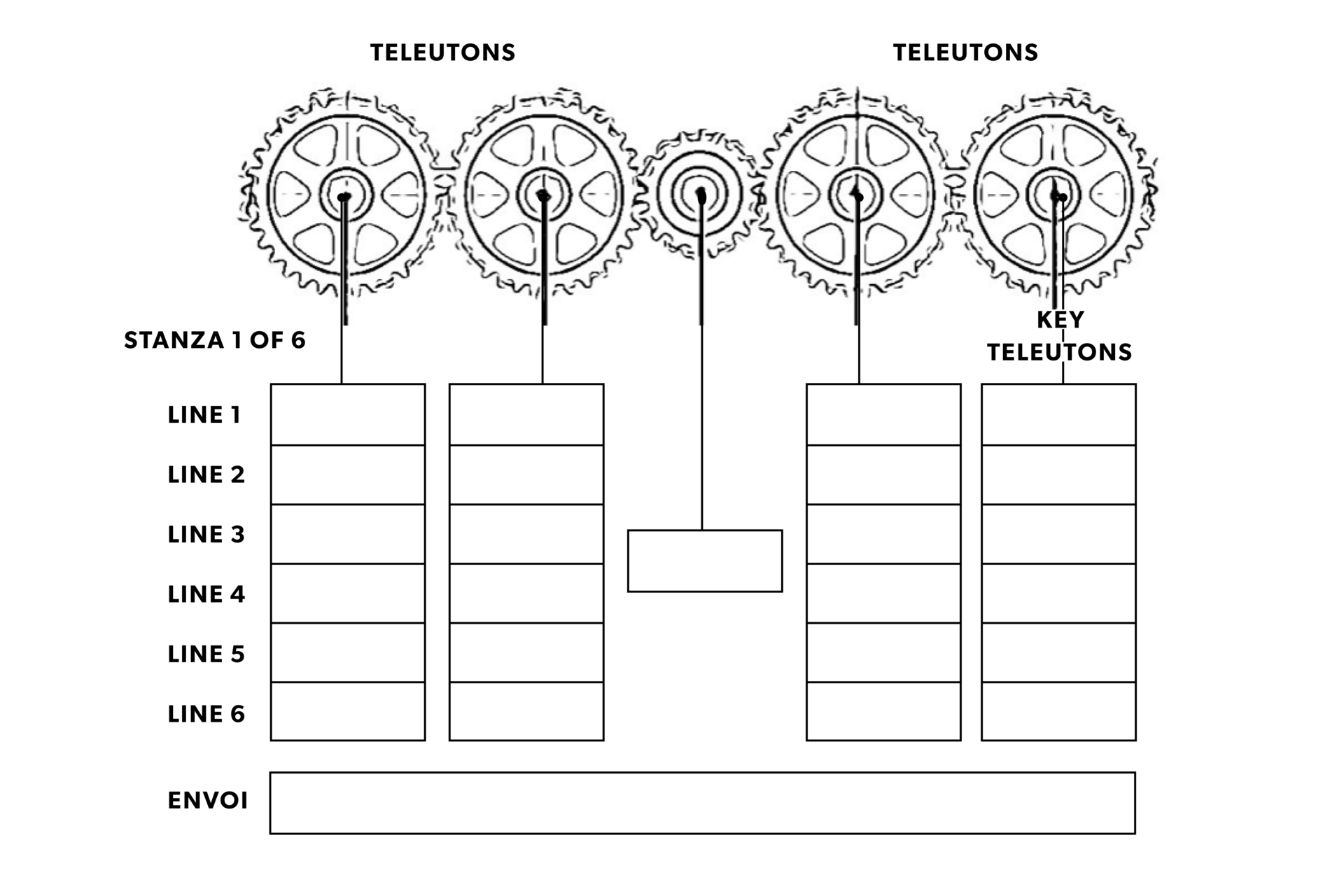

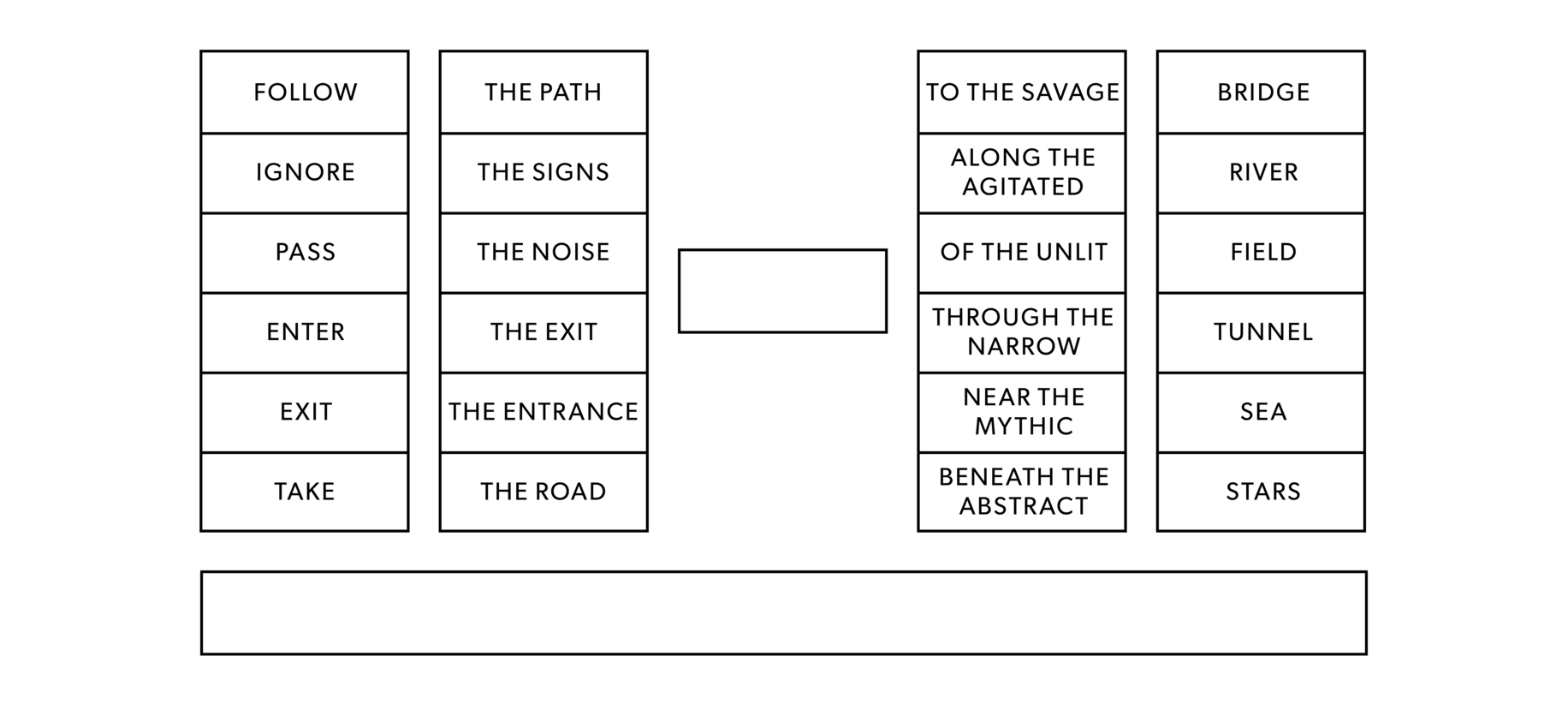

YOUR DO-IT-YOURSELF SESTINA ENGINE KEY

The traditional sestina (concocted by a French troubadour in the twelfth century) is a thirty-nine-line poem that repeats six end words (teleutons) in six six-line stanzas (sestets) in an interlocking cycle, and ends with a seventh three-line stanza (envoi) that uses all six teleutons. Like so:

stanza one: 1 2 3 4 5 6

stanza two: 6 1 2 3 4 5

stanza three: 5 6 1 2 3 4

stanza four: 4 5 6 1 2 3

stanza five: 3 4 5 6 1 2

stanza six: 2 3 4 5 6 1

stanza seven: three lines using all end words

The sestina’s numerological architecture and lexical repetition create a lyrical, potentially alchemical energy. The DIY sestina works like a linguistic slot machine of multiple teleutons rotating on the gears of your input.

If you are unable to grasp the DIY sestina engine concept, try constructing a three-dimensional model using paper, wood, or metal along with any additional necessary materials and ingenuity. Shape the material so that it is no longer two-dimensional. Make sure each of the five gears has a circumference of teeth and a hole at the center. As soon as the middle gear speaks, carefully cut out the spoke holes. Feed your words into the teeth of the engine.

DIY SESTINA: WHAT DOES THE PIECE REMIND YOU OF?

The Negro in an African Setting by Aaron Douglas, 1954:

Take the hazy overlook toward the Negroes in the stars.

Stay on the overlook towards the mouth of the river.

Pass the Negroes parked in the dark & hiding in the field.

Take River Styx Boulevard to the pyramid, go through the tunnel.

Pass through an agitated rain forest & get on the ramp to the bridge.

After several hours on the bridge, take the exit to the sea.

Icarus by Henri Matisse, 1947:

Take the unlit shape of one of the blacks you see

In the scene & make a Henri Matisse collage of six yellow stars.

Stencil the unlit figure on all the crosswalk signs for drivers.

Hello to the Negroes parked in the dark & hiding in the field.

Follow the Matisse hiding in Hank Willis Thomas with tunnel

Vision. After the last crosswalk sign, take the next bridge.

Mecklenburg Autumn: Heat Lightning Eastward by Romare Bearden, 1983:

Do not enter the river. Relax on a quilt on the bank with your bride.

Leave the door of your gray house open for all to see.

Take eight-hour siestas whether the sky fills with lightning or stars.

Follow the eyes of your bride watching trouble rise in the river.

Take time admiring how good your guitar makes you feel

Passing a hand over its strings as your bride hums its tune.

Going Home by Jacob Lawrence, 1947:

Head along the river until you come to the long railroad tunnel

Through the mountain, take the second left after the bridge.

Follow the signs through towns no one built to withstand a siege

Of poverty or weather. Employ tunnel vision amid the stares.

Should you pause for rest. Do not enter the river.

Hello to the Negroes resting on the train riding over the field.

Face Down by Martin Puryear, 2008:

Head downhill into the valley avoiding where floodwaters fill

The lanes. Every hole in the ground is an unfinished tunnel.

Take a shovel for burying seeds & bodies beneath the bridge.

Take just the front half of your face & say what you see

When you lower it into a basin of river lit by lightning & stars.

Follow signs of the creatures who live at the edge of the river.

Haystacks by Henry Ossawa Tanner, ca. 1930:

Stay on the overlook toward the mouth of the river.

Pass the Negroes parked in the dark & hiding in the field.

You can almost see Face Down in Haystacks if you use tunnel

Vision. Hello to the Negroes crossing a bridge.

Take the shape of one of the Negroes you see.

Take the overlook whether the sky fills with lightning or star

Born in Columbia, South Carolina, Terrance Hayes earned a BA at Coker College and an MFA at the University of Pittsburgh. In his poems, in which he occasionally invents formal constraints, Hayes considers themes of popular culture, race, music, and masculinity. “Hayes’s fourth book puts invincibly restless wordplay at the...

-

Related Collections

-

Related Articles

- See All Related Content