The Ghost Inside

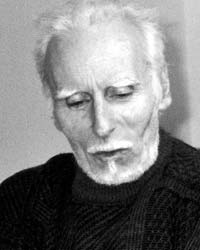

“I don’t want to be at peace,” Jack Gilbert pronounced shortly after his 80th birthday. Yet he has spent much of his life on remote Greek islands, on a houseboat in Kashmir, on a western Massachusetts farm, and in the remote outskirts of Sausalito, California, either alone or in the company of one other. He has never owned a home and has driven a car only twice. A sensible person might even say he’s sought a peace separate from the arena of the “career poets”—and maybe even separate from that of the career adult. But the unique kernel of Gilbert’s poetry is its fearless exploration of the adult heart. It takes a moment to have a fling or write one good line, but sustaining authentic emotional participation, as Gilbert has in his life as a poet, is terrifying and hard, and is practically a lost art.

“I don’t want to be at peace,” Jack Gilbert pronounced shortly after his 80th birthday. Yet he has spent much of his life on remote Greek islands, on a houseboat in Kashmir, on a western Massachusetts farm, and in the remote outskirts of Sausalito, California, either alone or in the company of one other. He has never owned a home and has driven a car only twice. A sensible person might even say he’s sought a peace separate from the arena of the “career poets”—and maybe even separate from that of the career adult. But the unique kernel of Gilbert’s poetry is its fearless exploration of the adult heart. It takes a moment to have a fling or write one good line, but sustaining authentic emotional participation, as Gilbert has in his life as a poet, is terrifying and hard, and is practically a lost art.

Gilbert was born in Pittsburgh in 1925 and grew up in the East Liberty district. His father worked in the circus for a time and died after falling out the window of a Prohibition-era men’s club when Jack was 10. After failing out of Peabody High School, Gilbert sold Fuller brushes door-to-door, worked in steel mills, and accompanied his uncle to fumigate houses, a job he began when he was 10 years old. “The cyanide could knock you out with just one breath, and in a matter of minutes you’d be dead,” he said in 1991. “It was an eerie way to grow up.”

He was admitted to the University of Pittsburgh because of a clerical error, where he began writing poetry (having previously written only prose) and earned a B.A. in 1947. After several years in Paris, Aix-en-Provence, and Italy—a chapter notable for his relationship with Gianna Gelmetti, the first of the three women who appear in his best love poems—Gilbert made his way to San Francisco, where the Beat and Haight-Ashbury countercultures were beginning to thrive.

A word about the women in Gilbert’s love poems before I go on. More than a few readers bristle at Gilbert’s apparently “antifeminist” poems. Women appear as totem creatures of mystery and beauty in poems like “Dante Dancing,” “Finding Eurydice,” and “Gift Horses,” but I am convinced that conventional feminism is the wrong filter through which to read these works. In response to a question about his elegiac poems written for his lost wife, Gilbert explained: “It was about grief, not about me.” Despite relationships that had all the signs of intimacy—with Gianna, Linda Gregg, and Michiko Nogami—Gilbert found the women he “knew” unknowable. And so he may write: “We are allowed / women so we can get into bed with the Lord, / however partial and momentary that is.” In the introduction to his own poems in the 1983 volume Nineteen New American Poets of the Golden Gate, Gilbert wrote: “I relish the physical surface of a woman, but I am importantly haunted by the ghost inside.”

Back to San Francisco. Gilbert lived in the Bay Area for 11 years, from 1956 to 1967, during which time he attended San Francisco State, worked with Ansel Adams, took Jack Spicer’s magic workshop, and enjoyed a years-long friendly argument about poetry with Allen Ginsberg. As the story goes, Gilbert didn’t like much of Ginsberg's work until one day when Ginsberg walked through a roadless and undeveloped area of Sausalito to Gilbert's cabin. He read aloud from two pages of poetry he’d just written.

Gilbert liked it. It was the beginning of Ginsberg’s iconic poem “Howl,” read publicly for the first time in 1956 to wild acclaim, and published in 1958. Four years later Gilbert’s first book, Views of Jeopardy, won the Yale Younger Poets Prize and was nominated for a Pulitzer. Gilbert enjoyed a year and a half of stateside fame, then won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1964 and left for Greece with the poet Linda Gregg. Six years would pass before he returned.

Gilbert wrote poems in Greece (and Denmark and England) that became Monolithos, his second book, finally coaxed into publication by editor Gordon Lish in 1982, 20 years after Gilbert’s debut. (Lish wrote a one-sentence essay for the New Orleans Review about Gilbert’s poetry. It read: “Why I like Jack Gilbert’s poetry and why I think Jack Gilbert is one of the best American poets and why I publish[ed] Jack Gilbert’s books is, was, and shall be to bring about the embarrassment of the power of discrimination in force in the assembly of fucking Harold Bloom’s fucking canonicity list. The End.”) That book, too, was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize—as well as the National Book Critics Circle Award. By then, Gilbert had separated from Gregg and married Michiko Nogami.

In 1982, after only 11 years of marriage, Michiko died of cancer at age 36. Gilbert next published a limited-edition volume called Kochan, a collection of elegiac poems written for Michiko, whose ghost would inspire what many call his best love poems, written in the early 1990s. Those poems constitute much of Gilbert’s third book, The Great Fires, which appeared in 1994. By this point he had been teaching from time to time, stretching the money in order to live quietly abroad, writing.

Last year Gilbert turned 80 and published his fourth book, Refusing Heaven. Form appears incidental to content in the new poems, as ever in Gilbert’s work. In an interview in the 1990s Gilbert said, “Mechanical form doesn’t really matter to me. . . . Some poets [write within a form] with extraordinary deftness. But I don’t understand why. . . . It’s like treating poetry as though it’s learning how to balance brooms on your head. . . . It’s like people who think sexuality is fun. Sure, it’s fun, but it’s a way of getting someplace, not just running to the corner for a little spasm.”

There are no little spasms in Gilbert’s poems—just giant ones, the immeasurable subjects of love and death, quiet but also somehow deafening. Gilbert’s is an aesthetic of exclusion. “There is usually a minimum of decoration in the best,” he has said. “Both the Chinese and the Greeks were in love with what mathematicians mean by elegance: not the heaping up of language, but the use of a few words with utmost effect.” Despite their streamlined appearance, Gilbert’s poems are not sentimental, obvious, or thin.

One of my favorite poems from The Great Fires contains even fewer elements than a classical haiku: the poem simply describes a man carrying a box. “He manages like somebody carrying a box / that is too heavy, first with his arms / underneath. . . . Afterward, / he carries it on his shoulder, until the blood / drains out of the arm that is stretched up / to steady the box and the arm goes numb. But now / the man can hold underneath again, so that / he can go on without ever putting the box down.” The lines appear almost inconsequential. But the title of the poem is “Michiko Dead.”

In a recent interview in The Paris Review, Gilbert asked, “Why do so many poets settle for so little? I don’t understand why they’re not greedy for what’s inside them. . . . When I read the poems that matter to me, it stuns me how much the presence of the heart—in all its forms—is endlessly available there.”

What is the most important thing a poet must seek, I asked him in February. His response: “Depth and warmth.”

Born and raised near Boston, writer Sarah Manguso earned her BA at Harvard University and an MFA at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her books include the poetry collections Siste Viator (2006) and The Captain Lands in Paradise (2002) and the story collection Hard to Admit and Harder to Escape (2007). Her work...

-

Related Authors

- See All Related Content

Jack Gilbert rocks! Thanks for sharing. We treasure his quest to define love.